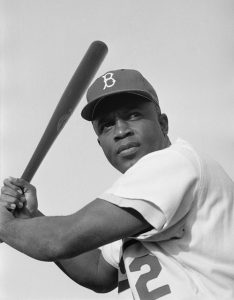

Jackie Robinson Revisited

The Jackie Robinson saga, biographer Jules Tygiel insisted before his untimely death in 2008, was comparable to an Easter/Passover service that invites public recollection every year. We must never forget what our country once represented and what it became thanks to the heroic life of Jack Roosevelt Robinson.

The Jackie Robinson saga, biographer Jules Tygiel insisted before his untimely death in 2008, was comparable to an Easter/Passover service that invites public recollection every year. We must never forget what our country once represented and what it became thanks to the heroic life of Jack Roosevelt Robinson.

Nobel Laureate Ernest Hemingway defined a hero as one who demonstrates “grace under pressure.” Our concept of heroism with a 1000 faces has changed dramatically from the ancient Greeks to contemporary America. Once the realm of aristocratic warriors, our pantheon is now peopled by women as well as men who rise from humble roots in a democratic society. Witness Jack Roosevelt Robinson. Ironically, a democratic society seems uneasy in the presence of heroes because, aristocratically, they loom larger than life. Thus, throughout our nation’s history, Americans seem eager to elevate the extraordinary individual followed by a propensity to topple him/her from the pedestal. In short, we are prone to smash icons. Some heroes, however, may go into temporary eclipse but their accomplishments and their traits resist our throwaway culture.

“A life is not important except in the impact it has on other lives” wrote Jackie Roosevelt shortly before his death in 1972. His was a short life by modern standards but what a life! In this commemoration—100 years later–we join Stephen Spender in contemplating “those who were truly great who from the womb, remembered the soul’s history… the names of those who in their life fought for life who wore at their hearts the fire’s center, Born of the sun they traveled a short while towards the sun and left the vivid air signed with their honor..”

Born in Cairo, Georgia on Jan. 31, 1919, Jackie would now be 93 years old. The youngest child of Mallie and Jerry Robinson, sharecroppers, he was an infant when his father, burdened by debt, abandoned his family. Undaunted, Mallie moved her children to Pasadena, CA to where her brother had relocated in quest for a better life. Mallie did double duty as a domestic and laundress. With meager savings, she bought a house in a predominantly white neighborhood: a source of conflict and confrontation with local racists.

Joining the Pepper Street gang, Jackie was incarcerated and humiliated after an incident provoked by a racial slur. Burning with a fierce anger that would smolder and erupt in later encounters, Jackie became a fierce competitor. As an athlete in public school, junior college, and UCLA, he proved superior in every sport: track, football, basketball, tennis, and baseball, possibly his weakest sport. He also excelled in golf and ping-pong. In his junior at UCLA, Jackie and future pro stars, Kenny Washington and Woody Strode dominated Pacific Coast college football. With his blazing speed and brilliant athleticism (he won four letters in four different sports; the first UCLA athlete to accomplish this Herculean task), Jackie won national attention.

Yet, several credits short of a college degree, he dropped out. Facing a bleak future, unable to secure a position in a major professional sport, Robinson drifted until the U.S. Army called. Eager to enter officer training, Jackie encountered rejection. Persistent, he asked heavyweight champ Joe Louis for help. The “Brown Bomber” contacted an influential person in Washington D.C and before you could say Jackie Robinson stole second base, he was indeed an officer as well as a gentleman.

Then “Old Man Trouble” arrived at Ft. Riley, Kansas. Lieutenant Robinson, as morale officer, protested the constraints placed on his fellow black soldiers access to the post exchange. This led to a volatile verbal confrontation. His Commander wanted Robinson to play football. Initially, compliant, Robinson balked when he was sent on furlough while the Fort’s football team played the all white University of Missouri. When Robinson returned from California, he resigned from the team. Unable to play baseball and plagued by a recurrent ankle injury, Jack receded from sports competition in the military. He conceded that his “heart was not in it.” Then, because JR refused, he was sent to Fort Hood (the site of a recent massacre perpetrated by a whacko psychiatrist or a Muslim fanatic; take your pick}. One day, riding on a military bus on the base, a bus driver ordered Jackie—sitting next to a light-skinned black woman married to a fellow officer—ordered Robinson to the back. Fully cognizant of his rights, Lieutenant Robinson naturally balked. The “cracker” bus-driver pulled over and had him arrested. Refusing to play an Uncle Tom, Robinson insisted on respect and his rights. He reprimanded a racist secretary and spoke mockingly to a subordinate MP Sergeant. The reward for such resistance was a court martial. Fortunately, a first-rate lawyer and Robinson’s athletic fame coupled with support from NAACP leaders led to a favorable verdict.

Acquitted, Robinson was offered a chance to lead a segregated force into battle abroad. Declining this dubious honor, he opted for a discharge. Newly appointed President of an all Black Methodist College in Texas, Karl Downs recruited the recently discharged officer to coach the basketball team. The college had only 300 students: only 36 of whom were male. Despite a small pool of male athletes, Robinson performed admirably. During a brief stint as basketball coach, Jackie tried out for the Kansas City Monarchs, once the elite team of Negro League baseball. Who recruited Robinson remains unclear. Monarch player-coach Newt Allen evaluated the raw recruit as “fast, heady, could hit a little, was a fine bunter and showed a good glove.” But his weak arm prompted Allen to advise Monarch owner, J. L. Wilkinson, the only white owner in that era, to use Robinson as a utility player. Subject to an oral contract, Robinson was offered a salary of $400 per month—a substantial salary by Negro League standards.

When the Monarchs’ regular shortstop Jesse Williams developed a sore arm, he switched to second base allowing Robinson to play short. In this position, Robinson received lots of favorable coverage from the Chicago Defender. Robinson started his short Negro League career on Sunday, April 1, 1945 in Houston Texas against a team of minor league stars. In a 14 inning 4-4 tie, rookie Robinson exhibited a good field, no hit performance. One week later, however, he banged out two hits and stole one base against the Birmingham Black Barons.

Soon the Pittsburgh Courier began covering every Robinson exploit. Ace reporter Wendell Smith even followed Jackie Robinson to Boston with Marvin Williams and Sam Jethroe in tow for an alleged try-out at Fenway Park on April 16, 1945. Arranged by City Councilman Isidore Muchnick who threatened to reinstate Boston’s Blue Laws regarding Sunday baseball unless blacks were given a chance to play for the Red Sox, this pseudo tryout proved that Boston’s baseball brass were opposed to integration as they turned a blind eye to Robinson’s splendid hitting and the talents of Jethroe and Williams.

Disappointed but undefeated, Robinson returned to Negro League play. Eager to learn, Jackie was a quick study. He had to hone baseball skills after a long hiatus from his UCLA baseball, his least effective sport in college. His batting average at UCLA in 1940 was an anemic .097. Sponge-like, Jackie rapidly absorbed the essence of Negro baseball: speed coupled with power. Conversely, he experienced acute dissatisfaction with the league’s constant travel, poor conditions on and off the field, lack of training. While he admired their baseball skills, Jackie disliked the behavior of his teammates and kept his distance from their bibulous carousing. They in turn found Robinson quick to anger and quite distant.

During one road trip through Oklahoma, Jackie ordered a white gas station owner to stop pumping gas after he and teammates were refused admission to a “white only” bathroom because the one consigned to “blacks” was out of order. Monarch room-mate Hinton Smith observed Jackie’s courageous stand and informed John “Buck” O’Neil. Another teammate Othello Renfroe remembered Robinson’s anger in similar confrontations with gas station attendants in Mississippi. On the field, Robinson’s offensive skills exceeded those on defense. Due to football injuries, his arm from deep short did not always find its mark, accurately. In one double-header against the Homestead Grays, he banged out seven consecutive hits but poor fielding contributed to twin losses. Against a Navy All-Star team in Boston on Braves’ Field, in mid-August, Robinson got two hits and stole three bases, including a theft of home in leading the Monarchs to a 11-1 victory.

In that abbreviated but stellar season, according to pioneer historian Robert Peterson, in 41 official games, Robinson hit a team-leading .345 with 10 doubles, 4 triples, and 5 home runs. Stout and Johnson claim a higher batting average at a robust .387. Biographer Arnold Rampersad notes that the Monarchs played 62 official games and about 20 games off the record with 32 wins. Whatever the precise numbers, Robinson evoked attention from one major league scout, Clyde Sukeforth of the Brooklyn Dodgers, an emissary of that “ferocious gentleman” Wesley Branch Rickey. Fortified by City Council and New York State legislation (Quinn-Ives Law, 1945), Rickey determined to sign a player of color. Summoned to 215 Montague Street in Brooklyn, Robinson and Rickey engaged in an historic exchange. Rickey laid out the ground rules for a “Noble Experiment” to break the racial barrier in baseball. JR complied with Rickey’s Christ-like turn the other cheek terms for starters.

Rickey chose Jackie Robinson for the right reasons. As a former army officer and a current gentleman, he was mature. Having lettered in four varsity sports at UCLA, Robinson was an outstanding athlete. In resisting “Jim Crow” constraints in the Army leading to a court martial, he demonstrated couorage; in the elegant words of Ernest Hemingway, Robinson personified “grace under pressure.” No doubt, Branch Rickey also appreciated that Robinson had attended college, that he was articulate, and that he was engaged to be married to Rachel Isum. Finally, Robinson neither smoked tobacco nor drank alcohol.

An agreement reached in August but consummated and publicized on October 23, 1945 sent Robinson to Montreal’s Triple A Dodger farm team in Montreal for the 1946 season, where he “tore up the pea patch” [in the words of peerless broadcaster Red Barber]——leading the International League in hitting at a .349 clip, scoring 113 runs, stealing 40 bases (second only to teammate Marv Rackley), fielding his second base position brilliantly, and sparkinging his team with timely hits and expert defense to a come-from-behind Little World Series victory over the Louisville Colonels, a top Red Sox and rabidly racist farm team.

In 1947 “when all hell broke loose” re. Red Barber, Robnson joined the Brooklyn Dodgers. Again “with grace under pressure,” he met every challenge and attempted “Beanballs” with unflagging determination. Despite external enemies (threatened boycott from Phillies, Cubs, and Cardinals) and within (Dixie Walker, Eddie Stanky, Bobby Bragan, and Kirby Higbe), he excelled. He hit .297, scored 113 runs, stole 29 bases and earned Rookie of the Year honors. During that turbulent first season, Robinson earned the support of several team-mates, namely, Ralph Branca, Duke Snider, George Shuba, Gene Hermanski, Pee Wee Reese. In the ’47 World Series, he drove Yankee catchers crazy with his base-running antics. Although the Bronx Bombers won the seventh deciding game, 5 to 2, Robinson’s narrative dominated. He was voted America’s second most popular personality: second only to crooner Bing Crosby. Even his alleged Dodger adversary Dixie Walker came to respect Robinson with these words:

I’ll say one thing for Robinson, he was as outstanding an athlete

as there ever was. He had the instinct to always do the right thing on the field. He was a steamwinder of a ballplayer. But, you know, we never hit it off very well…but Jasckie was avery antagonistic person in many ways, at least I feel he was. Maybe he had to be to survive. The curses, the threats on his life. I don’t know if I could have gone through what he did. I doubt it.

Robinson’s subsequent career spanning ten years produced high achievement: a .311 lifetime BA, six pennants (two more were lost on the final day), a World Series win in 1955: Brooklyn’s only one. Voted National League MVP in 1949—a first for African-American players, JR hit a league leading .342, knocked in 124 runs, scored 122, and stole 37 bases. He smashed barriers on and off the baseball diamond. In 1953, he also broke the color barrier in St. Louis’s Chase Hotel just as he paved the way for desegregation in southern stadiums (one incident in New Orleans invites mention), civil rights legislation and judicial decision favorable to integration. Moreover, Robinson opened doors for future athletes of color and gender: brown, yellow, as well as black.

In business, he established positive precedents in corporate America, banking, insurance, construction, and politics. In sum, JR eschewed accommodation, deplored avoidance as he aggressively pursued social justice. He vigorously denounced Malcolm X’s anti-Semitism. Jews, he argued, are the allies of Blacks in their common struggle for equal rights. His first post baseball employer, William Black (ne Schwartz), his lawyer, his young correspondent Ron Rabinowitz, his first neighbors in Brooklyn and last ones in Stamford CT, singer Carly Simon’s family were Jewish. In addition, the Robinson family’s favorite place for R & R, Grossingers Hotel had a Jewish ambience. Indeed, it can be argued that Brooklyn provided the best environment for the Rickey-Robinson “Noble experiment” because of the ethnic mix and working class composition of its populace, largely immigrant and Jewish.

Jackie spurned accommodation: chiding the NAACP, vintage 1960s for its inability to march swiftly and appeal to more militant youth. Thus, he opted for an aggressive strategy: marching with Dr. King and raising funds for SCLC and other CR organizations that promoted progress through education, in short, leading by example.

The struggles that JR faced–the victories on and off the field of dreams–brought tragedy along with triumph. He lost his first child and namesake first to drug addiction; then to death in an auto wreck on the Merritt Parkway at age 26 in 1971 triggered guilt and heartache to this “Lion at Dusk” in the words of author Roger Kahn. Illness—diabetes and heart trouble—plagued Jackie in his post baseball life.

Jackie Robinson and a select few of athletic heroes defy the debunkers and compel us to contemplate their cultural roots and historical branches. With amazing grace under enormous pressure, Jackie changed the game bringing Negro League style–speed coupled with power, daring with panache–to the center of American baseball. Not only did Jackie change the game; he also transformed the nation. In ten years as a Dodger, he led his team to six pennants and one World Series triumph in 1955. His on-base percentage of .411 ranks historically among the best twenty five.

After a dispiriting seventh game loss to those “Damned Yankees” in 1956, Robinson retired with a hefty lifetime batting average of 311. As Winston Churchill once warned, however, statistics convey only half-truths. Jackie’s contributions transcend quantification. Unwilling to be bartered to the Giants, #42 hung up his spikes. Robinson went on to break barriers in business, banking, broadcasting, construction, the baseball dugout and the executive suite. Our nation’s premier athlete–the only UCLA Bruin to letter in four sports: track, football, basketball and baseball–he fulfilled the American dream: rising from rags to riches. Rookie of the Year in 1947, Most Valuable Player in 1949, Hall of Fame in 1962, Robinson seemed to have it all.

It was an American success story scripted from vintage Horatio Alger just in time for the confrontation with the USSR, almost too good to be true. And it was. The truth was more complex, more disturbing. Racism did not vanish. African-Americans did not zip up to that elusive room at the top. Jackie became a pawn in the Cold War. Persuaded to testify before the infamous HUAC, he refuted Paul Robeson’s contention that Black soldiers would not fight against the Soviet Union. Set up by his “Baseball father” Branch Rickey, an arch Republican and Urban League Director Lester Granger, he denounced “the siren song in bass”—a reference to Robeson’s brilliant voice. Warmly hailed by the establishment press and mildly criticized by the black press, Jackie urged legislators to remove the shackles of Jim Crow. That progressive message was downplayed in favor of his strong patriotic pitch.

Years later, shortly before he died, Jackie apologized for his cruel criticism of Robeson but not for his staunch defense of America. Here, culled from his autobiography are his reflections:

That statement was made over twenty years ago, and I have never regretted it. But I have grown wiser and closer to painful truths about America’s destructiveness. And I do have an increased respect for Paul Robeson who, over the span of that twenty years, sacrificed himself, his career, and the wealth and comfort he once enjoyed because, I believe, he was sincerely trying to help his people.

He realized, after all, towards the end of his monumental life and his painfully honest book that he “was a black man in a white world. I never had it made.”

To be sure Robinson opened doors; but disparities between rich and poor, white and black, urban and suburban grew wider. The turbulent 1960s–featuring the new gods of relevance, pleasure and celebrity–cast aside old heroes befitting a throw-away culture, among them: Jackie Robinson.

Robinson did not manage or coach. Some labeled him a troublemaker and the label stuck. Youngsters cited his conservative politics and his support of Richard Milhous Nixon. Robinson did not fit the radical chic or the new sexuality. As a devoted family man, business executive, Rockefeller Republican, he must have seemed the ultimate square. Obscured by the high salaried celebrities and targeted for low blows from mindless militants, Jackie went into temporary eclipse. A major study in 1965, The Negro American edited by preeminent scholars: Talcott Parsons and Kenneth Clark contains no mention of Jackie Robinson! Other tomes demonstrated a strange indifference to this noble giant in Dodger uniform. An inane remark by a contemporary player coupled ignorance with amnesia. And this failure of memory was shared by many.

A reappraisal started in the 1970s with the advent of Roger Kahn’s brilliant The Boys of Summer and continued in the 1980s with Jules Tygiel’s magisterial Baseball’s Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson And His Legacy. Maury Allen, Peter Golenbock, Bob Lipsyte, and Carl Prince added to this impressive genre. These books demonstrate the danger, courage, and cost of this noble experiment. Martin Luther King Jr. confided in Dodger pitching great, Don Newcombe that Jackie Robinson was indispensable. In effect, he confessed: no Robinson, no King–a statement substantiated by the Rev. Wyatt Tee Walker, a close associate. Quoting the Civil Rights leader, he said: “Jackie Robinson made it possible for me in the first place. Without him, I would never have been able to do what I did.”

Indeed, crossing the color line in baseball, the national pastime, in 1947 was more dangerous than Neil Armstrong’s first footfalls on the silvery moon in 1969. While the astronaut had the support of all Americans, Jackie Robinson–with the exception of mentor Branch Rickey, beloved wife Rachel and a few crusading journalists–basically ran alone. He had enemies, a fifth column, on his own team. He had to overcome the stereotype of Sambo, Amos & Andy, Aunt Jemima and Uncle Ben. Media forged manacles had captured the soul of black folks and had beamed a benighted image of the docile Negro.

Throughout the sports arenas, before Robinson, black athletes projected personas of brute force like Jack Johnson and Joe Louis or gifted clowns like the Harlem Globetrotters. Even the enormously popular Joe Louis was painfully inarticulate. Then came Jackie: daring, daunting, dignified. With the solid stroke of his bat, a spectacular snatch of line drive heading over second base and a sensational steal of home, Robinson vaulted into our national psyche. Off the field, his high-pitched tenor voice spoke cadenced sentences which parsed and imparted incisive commentary. Not only did Jackie redefine baseball culture by bringing a new combination of speed, power, and style to the national game; he also destroyed the way blacks were perceived. Italian, Irish and Jewish kids–I was only eleven when Robinson joined the Dodgers–rooted for Robinson and our erstwhile Bums. We began to see our Brooklyn neighbors and Negro classmates differently; once through a glass darkly; now, through a lens brightly. A pioneer on the frontier of race, ethnic, and ultimately gender relations, Jackie Robinson brought us closer to that holy grail of peace, justice and the American way. Bill “Bojangles” Robinson called Jackie “Ty Cobb in Technicolor.”

Our landscape is graffitied with celebrities instead of heroes. Historian Daniel Boorstin inferred that a democratic society bears an intrinsic bias against individual heroes. Earlier, our nation’s heroes arose from common origins Jackie Robinson powered by merit. Today, however, the celebrity often devoid of talent occupies center stage in both sports and entertainment. Character and achievement often play second string. These celebrities blur the boundaries between heroes and anti-heroes.3

Shortly before his death at age 53, nine days to be precise, Jackie appeared at a World Series game in 1972 to celebratory recognition of the 25th anniversary of his historic entry into major league baseball. He spoke briefly. Robinson thanked Captain Pee Wee Reese for his leadership and support; then pleaded for a black manager in the dugout and a Black coach peering from a third base perch to advance racial integration to a higher level.

Cincinnati Reds’ second baseman Joe Morgan (later a color commentator on a weekly baseball telecast) who proudly wore a uniform with his hero’s number 42 thanked him. Sportswriter Jim Murray, suffering from failing eyesight, greeted the legally blind Mr. Robinson with these poignant words: “Oh, Jackie I wish I could see you again!” To which Jackie replied “Jim, I wish that I could see you too.”

Nine days later Jackie died of a massive heart attack. Many fans came out to Riverside Church to see the body of Jackie Robinson lying in state. A young preacher, Jessie Jackson delivered the eulogy. The salient words culled from his tombstone 1919-1972:

On that dash is where we live. And for everyone there is a dash of possibility, to choose the high road or the low road, to make things better or worse. On that dash, he snapped the barbed wire of prejudice.

His feet danced on the base paths!

But it was more than a game.

He was the black knight

In his last dash, he stole home and Jackie is safe.

His enemies can rest assured of that!

Call me nigger, call me black boy! I don’t care!….

No grave can hold this body down because it belongs to the ages; and all of us are better off because that man with that body, that soul and mission passed this way.

On that dash, 1919-1972, Jackie changed history.

Thus, we return to the touch of poet Stephen Spender who guides us through the urban wilderness.3Robinson signed the vivid air with his honor. Forever fixed in the mystic chords of memory, he summons what Abraham Lincoln also called the “better angels of our nature.”

Thank you Jackie Robinson.